Fukuyama, Fred, and God

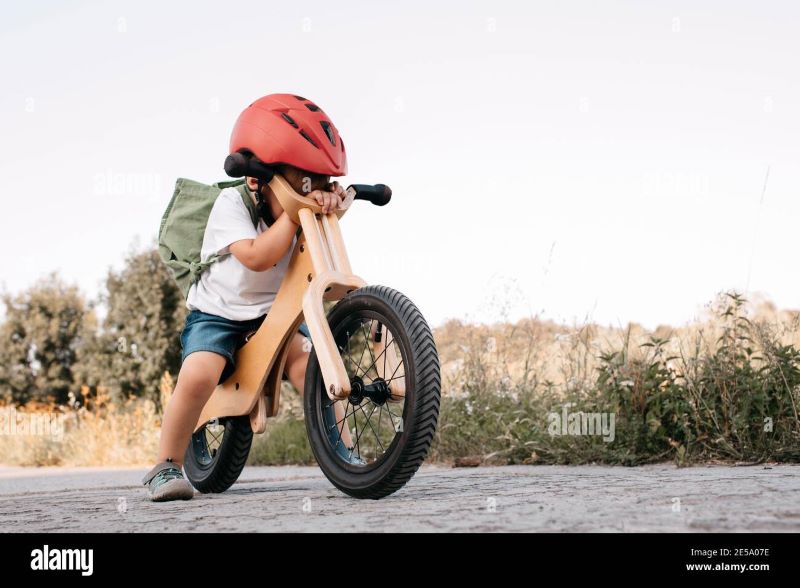

Sometimes, it's easy to forget what riding a bike as a kid felt like.

There's a simple freedom to it. The whole world becomes your neighborhood. Imagination spins with your wheels, revolutions carrying you through the unknown. City streets, country roads, gentle hills, shadowed alleys. Nothing in the world is beyond you.

It wasn't easy getting up on that bike, though. That meant something to you, way back when.

Using a theory of history, some German existentialism, and pictures I found on the Internet, I'd like to paint a picture of the day you get back on that bike. There are a lot of reasons why I want to do this, but first and foremost, I just like the idea of a world of kids on bikes.

It also just so happens to be the day you save the world.

Some background

In 1989, American author and cultural critic Francis Fukuyama wrote and published an essay titled: "The End of History".

What he describes is the end of a period of historical struggle for human beings, and the consequences of this End.

Fukuyama's theory is about a lot of things. Politics. Philosophy. History. Time, our place in it, and what that means. No mention of bikes; mostly, at its core, his theory is concerned with what happens when something Ends, and how we respond it to it.

There are three big points to know about The End of History. These are not the only points of this theory, but they're important to know, if you're gonna get back on that bike.

1. History was the struggle to get on a bike.

If you have learned how to ride a bike, you know there is a whole history to it. A story of challenge, of struggle. Trial and error, success and failure. Of scrapes, and falls, and near-misses, and finally, finally, finally, at last, the first real ride.

This is a major simplification, but for Fukuyama, all history before a certain point is basically the story of humankind trying to get on the bike. All of history, everything you can imagine in the human past, was us just trying to get up on the bike.

One day, we got up for the first time.

2. The End of History is us finally getting on the bike.

One day, after some struggle, you finally get up on the bike for the very first time.

This is a huge victory! You've been trying for so long, and finally, you're here. You've done it! Simple freedom awaits.

If you spent your whole life trying to get on the bike, though, and you finally do, it's a moment of victory---but a sober truth settles in: you have lost a major purpose. The struggle to get on the bike made you who you are, and now it's over. That doesn't mean that there won't be hills, or more falls and scrapes, or the occasional crash, but that major struggle, that period of development of you getting on that bike is done.

For Fukuyama, this is the End of History.

The specific point Fukuyama cites as us "getting on the bike" is the change in thought that occurred during the American and French Revolutions, which spread throughout the rest of the world. These revolutions successfully challenged and defeated the idea of the supremacy of kings, and enshrined the will of the people as main principle of organization.

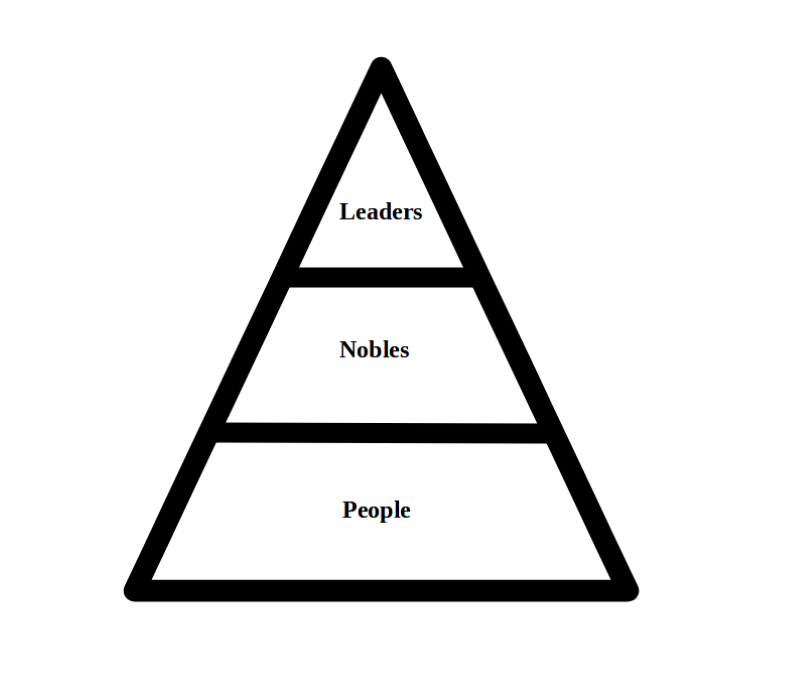

It made the baseline system of organization across the world go from this:

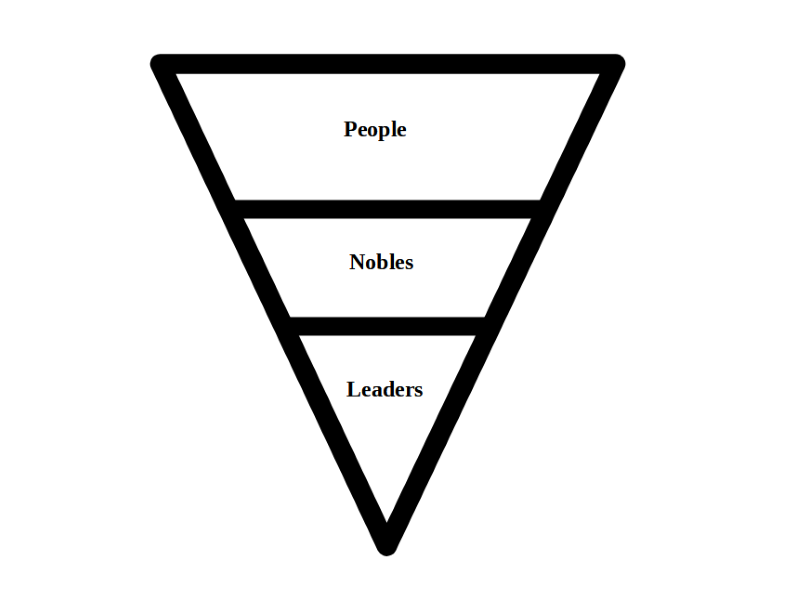

To this:

This is Fukuyama's theory stripped down to the bare essentials. Much like getting on a bike, we could talk about all the specific little movements and moments and terms, but really what's most important is the simple movement which changes everything.

Which leads us to:

3. All our history was the struggle to get on the bike. Now that we're on the bike, there's nothing left to do.

So, we struggled to get on the bike. We finally got on it!.

Now what? If all of our history was the story of us getting on the bike, what do we do now?

Fukuyama has an answer, and it's a little depressing:

“The end of history will be a very sad time… daring, courage, imagination, and idealism, will be replaced by economic calculation, the endless solving of technical problems, environmental concerns, and the satisfaction of sophisticated consumer demands. In the post-historical period, there will be neither art nor philosophy, just the perpetual caretaking of the museum of human history.”

“The End of History?”

page 13.

So, that's it. I lied. You'll never get on a bike again, or save the world. It turns out our whole purpose as human beings was to get on the bike, and now ironically, we did it, and we have nothing left to do. Nothing but work at Wal-Mart and go online shopping and watch an endless parade of sequel historical events---sequel wars, sequel financial crises, sequel pandemics, sequel politicians---march in front of us, dusty photographs from an album titled: "All You Ever Were Is Nothing You'll Ever Be Again."

Hey.

Wanna know a secret?

That's only half the story.

Fred Again

You may have heard the phrase “God is dead.” Though this had been said by others before, the person who made it famous was Friedrich Nietzsche, an existentialist German philosopher who did much of his work in the latter part of the 19th Century.

Fun fact: Nietzsche is also the originator of the phrase, “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.”

The full phrase, “God is dead, and we have killed him.” is often taken as a consummate example of nihilism, the belief that there is no inherent meaning to life. Like the End of History, nihilism is another "getting on the bike" moment. The final result of mankind's search for meaning is realizing there is no inherent meaning to life at all. Much like the End of History, nihilism extolls this conclusion as a finality, and a sobering truth we must all recognize.

Nietzsche is usually held as nihilism’s patron saint, and people use his beliefs as a way to bemoan a complete loss of any kind of hope in the world. God is dead, nothing means anything, history is over, I finally got up on my bike only to realize the process of getting there was all I had in the world, and there’s nothing left to do but put it away and mope around my existential neighborhood until I die.

Nietzsche was a nihilist, yes. And he did say that God was dead. He wrote about it –a lot.

For Nietzsche, however, these ideas were not just ends – they were beginnings.

In his theory of the death of God, Nietzsche isn’t saying that God, the metaphysical being, the Big One in the Sky, is dead. He’s saying a specific type of relationship with God is over.

The Death of God is kind of like realizing you don't need your parents' help to get on the bike anymore. Does this mean you don't need your parents anymore, or you stop loving them just because you got on the bike? No, not at all. But getting up on the bike for the first time as a kid is a small, but significant shift in your relationship with them. After your first steps and your first words, your first time on a bike is maybe one of the most significant parts of development as a kid.

At the time of his writings, Nietzsche was living in a Germany, a Europe, a World, fundamentally altered by human events. The renaissance of scientific thought and the Enlightenment, the American Revolution, Napoleon, as well as exposure to other religious ideas like Buddhism and Taoism.

No longer could, or would, people only go to their local priest for answers – now, there was a whole world of ideas to choose from. Kids on bikes.

In one way, Nietzsche found this terrifying. With the loss of God as the singular place people could go to for meaning, he feared the resulting psychological backlash would lead to existential horrors on a global scale.

He wasn’t wrong.

However, the death of God also provided a new way for people to navigate the world and find meaning for themselves. Overall, this was an event that inspired a kind of sober hope in Nietzsche:

“… when we hear the news that ‘the old god is dead’, [it’s] as if a new dawn shone on us; our heart overflows with gratitude, amazement, premonitions, expectation. At long last the horizon appears free to us again, even if it should not be bright; at long last our ships may venture out again, venture out to face any danger; all the daring of the lover of knowledge is permitted again; the sea, our sea, lies open again; perhaps there has never yet been such an open sea.’ ---”

-The Gay Science

page 280

Sounds like someone who just learned how to ride a bike for the very first time.

Kids on bikes

Whew. How's that for a spin around the existential neighborhood? It's been a while, I bet.

I believe, like Fukuyama, that the End of History is real. As real as getting up on a bike for the first time.

Unlike Fukuyama, and borrowing a bit from Nietzsche, I disagree that this End consigns us only to an eternal shift at Wal-Mart, or a never-ending parade of historical sequels.

Some part of our history has ended. We may not know what that means until much later; some formative period, though, has certainly passed.

So, yes, it is a real End. Life is full of them. With that first real ride, the history of you getting on the bike, all of what you did and who you were before, is now over. It is truly, history.

You cannot go back. It’s a little sad – but don’t worry. It will always be with you. Just like your bike.

And now.

Now you know how to ride a bike.

Now, there's a new day, a new purpose, a new beginning to a new history…

… deciding where to go first.

Toppa Publishing

About Toppa

Toppa Publishing is a pocket blockbuster publishing house. We’re here to create and find the next generation of American myths and great stories.

Contact the webmaster here: toppapublishing@gmail.com

Things I Like

- Cheeseburgers

- Cartoons

- Pokemon

- Halo 3